Moving In

and Moving Out

Understanding social exclusion and rural-urban migrant mental health in Shenzhen

A small public square bordered by 8 or so buildings and shops, full of functioning and broken bicycles.

A small public square bordered by 8 or so buildings and shops, full of functioning and broken bicycles.

A group of young employees at a beauty parlour practice corporate chants and anthems in preparation for their morning shift.

A group of young employees at a beauty parlour practice corporate chants and anthems in preparation for their morning shift.

A relatively quiet hour in a major retail street in Baishizhou.

A relatively quiet hour in a major retail street in Baishizhou.

The time is 9:03 am in Baishizhou, and we’ve already missed the morning exodus of people to their respective worksites and schools. Still, there is noticeably more commotion at this hour within the migrant-populated urban village than the trendy condominiums and amusement parks surrounding it.

On the outskirts of town in the Longhua Industrial Area, a dormitory for migrant construction workers is empty. A schedule pasted on the wall suggests that it’s already been 2 hours into the work day for its inhabitants. These scenes make up the heart of the largest internal migration event in the world and the human experiences within.

The common area of a dormitory, meant for eating and recreation.

The common area of a dormitory, meant for eating and recreation.

The kitchen of the same dormitory. Note the live chicken in the cage.

The kitchen of the same dormitory. Note the live chicken in the cage.

The dormitory's shower area.

The dormitory's shower area.

Shenzhen was first launched onto the global stage in the 80s, when it was designated the first Special Economic Zone (SEZ) through Deng Xiaoping’s seminal “opening-up” of the Chinese economy. Since then, it has become the third largest geographical contributor to the Chinese economy, serving as a testament to China’s success in adopting a mixed-market system1. Shenzhen’s rapid transformation from a fishing village into a bustling megacity was accomplished in less than 40 years, driven by the mass-migration of people from rural China seeking economic opportunities in the city. As of 2016, more than 287 million Chinese have become rural-urban migrants2.

Internal migrants are believed to be especially vulnerable to poor mental health due to social exclusion, defined in this essay as the absence of resources, rights, and goods, along with the inability to participate in the normal activities available to a majority of people in society3. However, the existing literature has relied overwhelmingly on quantitative methodologies. While these studies are powerful, there is much that they cannot capture - such as inconsistencies in the migrant experience across different identities of age and location, or the diversity of how migrants may respond to adversity. To help in illuminating these aspects of the migrant experience, our team received funding from the Richard Charles Lee Insights Through Asia Challenge in the Munk School. For the month of May, we travelled to Shenzhen and Hong Kong to speak with local stakeholders and to visit popular sites of work, life, and play. After more than 9 months of research, we present this essay - a snapshot of Shenzhen and its rhythms of migrant life, from day to night. Starting from now - at 9am in the morning in Baishizhou, Shenzhen’s largest and most famous urban village.

We venture further into the neighbourhood, where structural density restricts movement to only pedestrians and nimble two-wheelers. Scattered throughout the area are bulletin boards stuffed with colourful notices for newly available rental apartments. Overhead, black power lines which droop low into walking space form a network weaving buildings together. Residents have creatively (and dangerously) fashioned them into drying racks for washed clothing. On the ground level, every inch of space is utilized for retail activities. We noted clinics, hairdressers, aestheticians, short-stay hotels, electricians, daycares, food markets, restaurants, among many others.

With a population of 150,000 squeezed into just 0.6 sq km of land4, Baishizhou is 3.5 times more dense than Manhattan - the most congested county in the US. This density is a product of demand for affordable housing in Shenzhen. Once, neighbourhoods such as Baishizhou were situated on the outskirts of the new SEZ and offered cheap rent while being central enough to access the city’s opportunities5. This continues to hold true today, though the creep of the city’s economic expansion has manifested spatially - creating new pressures for urban villages as development efforts barrel towards a future of malls, parks, and luxury condominiums.

Urban environments have long been linked to increased mental distress for their lack of light, air pollution, crowding, noise, and limitations on autonomy and social activity6,7. As is characteristic for urban villages, Baishizhou’s streets are narrow and marked by closely-built mid-rise apartments - infamously named “handshake buildings” for the fact that one can easily reach out of their window to shake the hands of a neighbour in an adjacent building. To guard from prying eyes in such close proximity, most windows are covered by sun-bleached newspapers. As we weaved through the morning alleyways, the sounds and smells of residents cooking, cleaning, laughing, and shouting wash down from above.

Posters of cartoon characters emphasizing the importance of preventing household fires.

Posters of cartoon characters emphasizing the importance of preventing household fires.

A graphic PSA illustrates the horrors of reckless driving.

A graphic PSA illustrates the horrors of reckless driving.

The premium of space in Baishizhou means that, apart from profitable operations such as retail or rent, neutral space is hard to come by. Dr. Ran Maosheng, an expert on mental health in China from the University of Hong Kong, notes the importance of surroundings on community and notes that the government could “build a healthy community for these migrants… [by] constructing a special building, park, activity area, club, or library for these workers so they can make friends, meet partners, and read.” Apart from restaurants which open onto the streets and a nearby shopping strip with a computer game cafe, we note a lack of accessible communal space and a constant security presence.

As Chinese cities become beacons of modernity and progress, urban villages are seen as incongruent to that vision and have been blamed by the government and public alike for social ills such as crime and disease8. Though security cameras are a norm in major public streets in Shenzhen and other Chinese megacities, the number of cameras and police outposts within Baishizhou is significantly higher than average.

For rural-urban migrants working in construction, it is most common for the company to provide dormitory housing for the duration of the contract. This dormitory in Longhua is a single-floor building across a parking lot from a set of multi-level management offices. Inside the sleeping quarters, as many as 20 wooden beds fit inside a room, though some are utilized as storage shelves. While there seems to be little ability or regard for protecting private belongings, we spot packs of cigarettes strategically hidden inside half-cut iced tea bottles.

At one end of the common area, a new-looking ping pong table sits. The worksite manager remarks that it is now a mandatory requirement for dormitories to have equipment for recreational activities, though he also mentions that whether people actually utilize them is a different story.

A little-used ping-pong table in the common area of the dormitory.

A little-used ping-pong table in the common area of the dormitory.

When migrants live near worksites in the periphery of the city, it is accompanied by a degree of spatial and cultural segregation from city life. Not only are such locations difficult to navigate - there is no reason to leave the surrounding area. A source from the labour rights NGO, China Labour Bulletin, notes that comprehensive services such as hairdressers are often located nearby or provided by the employer themselves. In addition, migrants do not partake in the normal amusements of the city because “they do not have the time, money, or culture of consumption to be consumers in the city.” When contracts last months, this can mean spending most of their time within the confines of the workplace.

Just a couple of kilometres away, a young woman in a pink shirt and stylish wide-legged pants pushes her suitcase through an empty outdoor shopping complex. Drawn to the mall by a McDonald’s sign, she explains that she was hoping to eat something familiar and comforting for lunch after getting off an overnight bus earlier in the morning.

Miao Miao is part of a constant stream of migrants who settle into the Longhua area, looking for a job at any of the nearby technology factories. At the age of 27, Miao Miao describes herself as old, stating that her mother is often ‘restless’ about her unmarried status. While she says she disagrees with the expectation that she should already be married at this age, she acquiesces to her sister who is actively looking for a match for her in her hometown. When asked about future aspirations, she spoke with confidence about her plan to use her earnings from a year at the Foxconn factory to start a business back home.

Lunch with Miao Miao.

Lunch with Miao Miao.

Miao Miao’s situation is a prime example of the kinds of tensions and accommodations that exist between the social expectations and economic dreams of migrant women. On one hand, female workers face profound pressures to find suitable partners and settle down while they still have the capital of youth and beauty9. Yet increasingly, they are driven to find work out of precarity back home, or to establish an independent existence for themselves10. As noted by Jacka (2006)11, this results in a diversity of attitudes towards migration in young women. For some who wish to remain in the city, they view migration as a critical opportunity to escape domestic restrictions and to change their fate. These ambitions are frequently felled by the reality that female migrants experience gender-based discrimination, which can be aggravated by sexual exploitation and abuse. For some who hope to return to their villages, migration is seen as a temporary interlude, or a viable strategy for fulfilling domestic duties. Yet sometimes, even these accommodations have an uneasy conclusion. China is the only country in the world where the suicide rate of women is higher than men12, a finding largely driven by the outsized prevalence of suicides by rural women. Many of these acts are impulsive and motivated by violations of dignity, justice, and power within the family - of which frustrated migratory dreams are a contributing factor13.

The exterior of a closed wholesale store, located on the outer edge of the Longhua Foxconn campus

The exterior of a closed wholesale store, located on the outer edge of the Longhua Foxconn campus

One out of many recruitment centres in the area - empty in the morning hour. The boards up front contain listings for positions from different factories.

One out of many recruitment centres in the area - empty in the morning hour. The boards up front contain listings for positions from different factories.

While Miao Miao’s independent attitude is a source of her drive to live in the city, it also makes her reject the notion of contacting old friends she knows are in Shenzhen or making new friends in the factory. Nonetheless, after our conversation, she expressed how nice it was to talk to someone, and that her nerves had calmed.

As Dr. Ran Maosheng notes, coping styles can significantly affect an individual’s mental health14. Those who are likely to “smother their frustration in their heart” (闷在心里) are more prone to poor outcomes, relative to those who access and utilise social supports. Given the lasting centrality of the family as an institution in China, the presence - or absence - of harmonious familial relations is critical to mental health. Vast geographical divides between migrants and their families jeopardise the maintenance of healthy family life, which includes the ability to receive care. In the aftermath of the 2009 Foxconn suicides, Dr. Ran was asked to lead the investigative committee. One of the main issues uncovered was the lack of ability to communicate effectively with family who lived far away in inner provinces such as Sichuan or Yunnan. In the end, recommendations were made to Foxconn to explore relocating factories closer inland.

A different series of challenges arise for families who make the resource-intense decision of migrating together. These long-term migrants often harbour hopes of raising their children in the city to obtain a better future for them. This aspiration is on full display mid-day in Baishizhou, where groups of children in blue and white uniforms walk back from the bus stop to eat lunch at home.

For these children, attending a public school in Shenzhen is a feat and attending a private school is virtually unattainable. China’s household registration system, commonly known as the hukou, links access to citizenship benefits to one’s permanent place of residence. Even children of rural-urban migrants born in the city inherit a rural hukou from their parents15. As such, they are not prioritized for enrolment into public schools. A separate category of “migrant schools” have been established to fill this administratively-created gap, but they are often poorly resourced - reinforcing segregation of rural and urban populations16.

These adversities are especially stressful in a culture where the success of children is of paramount priority. As one migrant parent we spoke to described it - “All parents have goals for their kids... I want to try hard at my job to make money so they can have a better education and life. My kids are not only my pressure but also my motivation.”

A man operating his business of buying and selling old electronic parts out of a banned house, ducking from the rain.

A man operating his business of buying and selling old electronic parts out of a banned house, ducking from the rain.

The hukou system was established post-1949 to control rural-urban movement and maintain a robust agricultural base for industrialization17. It sorted citizens into binary categories of rural or urban. For urban hukou holders, their status grants access to subsidized housing and public services such as healthcare, educational benefits, and unemployment insurance in the city18. For rural hukou holders, such benefits are not provided due to the assumption that their agricultural background has made them self-sufficient19. As such, rural-urban migrants work in the city with no access to social safety nets, even if they have lived there for years20.

A cluster of houses, cordoned off by authorities. The homes are still in use, though passer-bys and residents are warned by signs that the houses are ‘dangerous’ and entry is banned.

A cluster of houses, cordoned off by authorities. The homes are still in use, though passer-bys and residents are warned by signs that the houses are ‘dangerous’ and entry is banned.

As China has pivoted its economic strategy to focus on growth by urbanization, reforms to the hukou system have loosened restrictions compared to the past. Nonetheless, reforms are uneven across jurisdictions and the granting of an urban hukou status is generally limited to those who meet certain education and skills requirements21. A migrant we spoke to shared that her husband was able to obtain a Shenzhen hukou right out of university, while the company she worked for helped her file the paperwork after several years employed there.

New economic forces have also changed migrants’ relationships with hukou. As rural status is bundled with land rights, long-term migrants with the option of applying for Shenzhen hukou must make a trade-off between increased urban rights or land rights. With skyrocketing housing prices in Shenzhen and a perception that the city life may not be more desirable than rural living, even those who would be able to receive urban hukou may hold out22. In 2018, only 34.9% of the permanent Shenzhen population had local hukou23. There are now increasing calls for policymakers to recognize multi-locality and move beyond transfer of hukou status as a basis to solve exclusion for migrants in the city24. As Dr. Ran Maosheng put it, “Just because the city is different from the country, doesn’t mean the country is worse.”

Washed school uniforms and shoes hanging on electrical wires and old security camera posts - re-fashioned into drying racks.

Washed school uniforms and shoes hanging on electrical wires and old security camera posts - re-fashioned into drying racks.

School shoes hanging off an old surveillance camera perch.

School shoes hanging off an old surveillance camera perch.

Archway from old building leading into an alleyway.

Archway from old building leading into an alleyway.

Early afternoon is a time of rest, and it is common in China for workers and students to have a nap before returning to work. In Baishizhou, a masseuse rests on her table with the door ajar in case any clients enter. At the Longhua construction site, the offices of managers all contain a bed or comfortable couch. While most of the workers at the site opt to take a long lunch break between 11:30-1:00PM, some opt to ‘add work’ (加班). We visited the worksite near the end of the afternoon break and and saw four males working overtime. They were quiet and focused, not speaking to each other or acknowledging the presence of us or the managers who accompanied us. Though the excavated portion of the road they were working on was not very deep, it was enough that a man perched on a makeshift scaffold with only a hard hat made us nervous.

Precarity in action.

Precarity in action.

Labour relations in China underwent a fundamental change following the introduction of foreign and private investment and the emphasis on export-driven growth. This orientation was solidified after China joined the WTO in 2001, consequently accelerating the pace at which migrant workers flocked to SEZs25. China maintains a comprehensive legal framework outlining protections of workers against exploitation including contracts, the right to be paid in full, protection against discrmination, and more26. However, the local governments which enforce the labour laws are often unable to do so from a combination of factors, including being under-resourced and officials who favour businesses over labour27. China Labour Bulletin notes reluctance from the government to strengthen legislation surrounding workers’ protection following the 2010 economic slowdown28. Heightened pressure to deliver on economic indicators has created a trend of relaxed labour governance and increased unrest.

Though government censorship of collective action makes it difficult to gauge trends, China Labour Bulletin’s (CLB) Strike Map collects recorded instances of protests and strikes across China, and they are rising. In 2018, 1,700 protests were recorded, up from 1,250 protests in 2017. In most instances, unpaid wages and social insurance pose major concerns. Regarding social insurance, which covers all aspects of a Chinese citizen’s pension, unemployment insurance, medical insurance, and housing subsidization, our source from CLB states, “Previously, workers may not even have social insurance, but in 2011 the Chinese government made social insurance payments from employers mandatory. But now, many employers are threatened by the economic slowdown and want to cut down excess contributions like social insurance.” Social insurance is included in the minimum wage in Shenzhen, meaning a typical retail worker will earn around $2700 ($500 CAD) after deductions29.

For workers looking to address their grievances, unionization is not an option. The officially communist Chinese state maintains a nation-wide, centralised trade union known as the All China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). CLB notes the following issues with this model, “For the moment, most migrant workers do not know trade unions exist or trust them. They do not view themselves as belonging to the union or that they can seek much help from it. China’s only trade union is state-sanctioned and headed by senior politicians. They often act to protect workers only after their rights are infringed but not before, and do not approach wage negotiation in collective ways and do it without worker participation. There are a lot of good achievements for the trade unions to say they have done but we think it is either not to the benefit of workers or do not have the participation of the workers it concerns.” For migrants who have shaped their lives around work, resolving labour disputes individually can be a major source of stress. Hong Kong-based Labour Action China has recently introduced psychiatric counselling for clients dealing with labour dispute cases where pressure from authorities and harassment from police weighs heavy.

In this context, an elevated risk of workplace accidents exists. During the afternoon lull, a manager we speak to at the Longhua construction site laments the standards of the industry. An older man in his 50s, he wears a short-sleeved shirt that is too large for his skinny frame and smokes the entire way through our conversation. Like others in his position, he is part of the generation which made the first wave of migrant workers and, despite a low level of formal education, worked his way up to his position. When we press, his sedated tone suggests he does not see that as worth elaborating upon. Instead, he emphasizes the construction industry’s poor compliance with legislation, such as those that prevent workers from working in extreme heat in the peak of the afternoon or when it is raining too hard. He grimly recounts instances wherein resulting workplace deaths end in a large payout to family members instead of procedural change. He explains that it is usually bearable for a large rural family to lose one child, especially if their death brings fortune to the family -“The families will dance on the worksite when they hear how rich they can become from death.”

Having just arrived in Longhua District, a large number of young men gather on the street, suitcases in tow.

Having just arrived in Longhua District, a large number of young men gather on the street, suitcases in tow.

A migrant waits for a Didi. Like many others in the area, he is carrying a suitcase - an indication of his recent arrival or impending departure.

A migrant waits for a Didi. Like many others in the area, he is carrying a suitcase - an indication of his recent arrival or impending departure.

The pull of the manufacturing industry on young migrants is on full display in the late afternoon rush out of Foxconn’s Longhua campus. Amidst the rush of cyclists and pedestrians, a charter bus parks on the side of the street and a flock of young men come off and unload their large suitcases. They sit on the sidewalk awaiting further action, passing the time by smoking or playing on their mobile phones.

The Chinese manufacturing industry is constantly on the lookout for labour to sustain the global middle class’ high-consumption culture. To fulfill these recruiting burdens, it has become common practice for vocational school students to be sent to Foxconn for a work term, regardless of whether that is congruent with their area of study or not. This is particularly concerning as Pun Ngai points out - students interning through an educational program maintain their student status and are not subject to Labour Law regulations30. For these students, who can be as young as 16, the excessive overtime and unfulfilling work can result in feelings of hopelessness. The suicides Dr. Ran was asked to investigate at Foxconn in 2009 were mostly of students31.

Nonetheless, the desirability of a job here is assumed to be universal. We approach two young women who are wearing Foxconn lanyards with the Apple logo, hoping to interview them. However, we find out that they are recruiters for Foxconn. Despite explaining that we are research students from Canada, she repeatedly asks if we are looking for a job throughout a good portion of the conversation. We had run into a similar situation earlier: when browsing job postings on a board in front of a recruitment agency, a very persistent agent insisted on adding us on WeChat and boasted that she could get us an interview the next day. Not to worry about the overnight stay - the employer will take care of it and we could start work immediately if the interview is successful. At no point did our delayed grasp of norms, accented Mandarin, use of English, and way of dressing, change the deep underlying assumption that everyone in the area is looking for employment. This constant flow of migrant labour creates a transitory state in which jobs can be easily found and workers can be just as easily replaced.

It’s 5:30pm, and the setting sun in Dafen Village has indicated the end of the work day for the residents. On the streets, young children play together under the casual supervision of their parents, who are socialising. Among Shenzhen's urban villages, Dafen is unique for being known as the world’s art factory. Official reports claim that it supplies more than 60% of the global painting market annually32. Walking around the village, we spot artists painting in alleyways, working concentratedly in tiny studios and completing commissions in formal shops. These range from originals to replicas to more unique ‘inspired’ pieces. (In one shop, we saw a replica of the Mona Lisa next to a minion made out to look like the Mona Lisa.)

With dinnertime nearing, we receive a WeChat message from Yiyi summoning us to her restaurant so we can avoid the evening rush. We had stumbled upon her unpretentious but bustling vegetarian spot earlier in the day while traversing through some backstreets, and managed to squeeze into a communal table for lunch. As the only foreigners in the restaurant, conversation quickly flowed between us and the others at the table - a mother with her daughter, a young woman, Yiyi and her husband. We learned from the group that they are all artists from disparate parts of China who have come to Dafen to further their careers. Despite having differing preferences over food, art, and popular culture, the group appears to have found a strong community in the village - with this restaurant being a key gathering place.

A regular customer enjoys dinner at Yiyi's restaurant.

A regular customer enjoys dinner at Yiyi's restaurant.

While the fragrant rice, warm broth, and huge assortment of vegetarian dishes provides a compelling reason in itself for the community to congregate around the restaurant, there are also several other qualities that make it so unique. Yiyi and her husband had gotten the idea to start the restaurant due to a lack of affordable vegetarian options in the area. At around $2.50 CAD for a complete meal, it is a bargain. A trust system is at the heart of the restaurant, in which customers are allowed to serve themselves and pay the specified amount at their own initiative. The reason for this, as Yiyi explained to us, was rooted in practicality: it had just gotten too much work to serve customers individually. However, she noted that the change had resulted in more willing offers to help in any possible way from customers, including helping her tidy up and moving furniture around.

At this restaurant, customers are free to serve themselves and pay at their own initiative.

At this restaurant, customers are free to serve themselves and pay at their own initiative.

In assessing the literature, an understanding emerges that the social reality of rural-urban migrants is best characterised as one of exclusion. Through low wages, isolated housing, long working hours, and stigma, migrants are economically, psychically, and physically excluded from the norms of city life. However, situations like the one in Dafen complicate this conclusion. Shenzhen is an ‘immigrant city’ unlike any other in China. Nearly 70% of all residents are migrants, a proportion 20% to 30% higher than that of China’s other major cities33 - and this figure is only set to increase. Our informants report that this defines Shenzhen as a city of and for migrants, transforming its character.

A couple get ready to reopen their shop for the evening crowd.

A couple get ready to reopen their shop for the evening crowd.

For one, Shenzhen is the only city where the local languages of the province such as Cantonese are not the main language - Mandarin is, as it is the lingua franca of migrants from all over China. Accents are usually a powerful determinant of inclusion and status for migrants34. In Shenzhen however, they may reveal a person’s origins but less about their level of ‘belonging’ to the city, given the wide diversity of accents spoken and the lack of a ‘standard’ to acclimatise to. To our surprise, our informants were also unanimous that there was little to no discrimination based on provincial accents - though this is contradicted by the literature35, suggesting that at most this a phenomenon specific to cities like Shenzhen.

This is not to say that Shenzhen is a city where migrants do not experience discrimination or exclusion. Instead, it is likely that the real inclusions and exclusions happen along other divides - most notably gender, age, and education. As our contact from China Labour Bulletin explains, younger generations of migrants have greater desire and means to be included within cities - for example, through their literacy and affordance of trendy clothing, grooming, or recreational activities, and their increased ability to negotiate for better working terms. Comparatively, older migrants are less willing and able to adjust their lifestyles to match those recognised by city-dwellers, making them more easily identifiable as outsiders.

A group of residents gather outside a shop for a game of cards.

A group of residents gather outside a shop for a game of cards.

A migrant’s educational qualifications can also greatly affect their mobility within the city. As previously mentioned, Shenzhen’s reforms largely serve “top talent” such as university graduates or overseas students - granting them hukou over lower-status workers36. The use of education as a filter necessarily implicates class and wealth as a determinant of whether or not migrants can receive social services in the city, facilitating status-based exclusion.

These findings point to the decreasing usefulness of understanding migrant life through the lens of a migrant and non-migrant, or even hukou and non-hukou binary. With increasing urbanisation, hukou reform, and an expanding middle class largely driven by migrants, many of China’s cities will increasingly resemble Shenzhen - suggesting that the diversity of migrant experiences within Shenzhen can serve as a vision of China’s urban future.

Shenzhen’s Luohu District is its oldest, though one would not be able to tell given the number of skyscrapers which obscure the night sky. With exteriors of gleaming glass and large LED panels, some buildings even have sophisticated light and laser shows - the lights of which diffuse with air pollution to give the sky a hazy glow. From the taxi, we note that the roads we drive on are frequently flanked on both sides by fencing - concealing malls, residences, and transport in development. Curiously, these fences are not covered in advertising. Instead, they carry text and illustrations extolling the Confucian virtues of filial piety and propriety, or powerful messaging in line with China’s recent anti-crime campaign, phrased as a “war to sweep out darkness and remove evil”37.

A banner hung on an overhead bridge outside the south gate of the Foxconn factory. It states: “Resolutely sweep out evil forces and strengthen the people’s sense of luck, safety, and satisfaction from gain”.

A banner hung on an overhead bridge outside the south gate of the Foxconn factory. It states: “Resolutely sweep out evil forces and strengthen the people’s sense of luck, safety, and satisfaction from gain”.

This messaging couldn’t seem further removed from the grandeur and cleanliness of our destination - the MixC. A sprawling complex spanning more than 200,000 square metres across six floors, it contains an intimidating mix of luxury stores and restaurants, including the largest Gucci and Prada stores in the entire Asia Pacific region and an ice rink.

Shiny office towers surrounding the MixC. In the foreground, a preserved structure alludes to the history of the area.

Shiny office towers surrounding the MixC. In the foreground, a preserved structure alludes to the history of the area.

Scenes like these are examples of how the Chinese dream has been conceptualised. On a national level, the Chinese dream is a narrative about rejuvenation from the immediate and indirect effects of imperialist humiliation - which included the devastation of social order and cultural capital38. As the signature ideology of the Xi administration, the Chinese dream therefore serves to direct policy in matters as diverse from foreign affairs to land rights39.

At the individual level, many have arrived at their own definition of the Chinese dream. For some migrants, this dream is maximalist - the desire is to become ‘a big figure’ who is able to comfortably afford and consume prestigious styles of dress, dwelling, and cuisine as offered by places such as MixC40. For others, they may have dreams that are more modest in size, but not in diversity - instead of desiring a ‘great’ life, they may aspire for a ‘good’ one, seeking a house of their own, entry into the middle class, or financial independence from their children.

Relaxing in the man-made jungle outside the MixC.

Relaxing in the man-made jungle outside the MixC.

To what extent, then, are these dreams achievable? To be certain, many migrants do succeed - against all the odds - to achieve the lives of prosperity and stability they desire. As our contact from China Labour Bulletin notes, a significant number of these migrants even return to their hometowns to create companies and jobs - sharing their fortune with others. But while the lifestyles and ideals that compose the Chinese dream have become widely distributed, it is evident that the actual means to achieve these aspirations are unevenly available. For parents looking to give their children the advantage of an education in the city, unwelcoming public school systems and prohibitive costs of private schooling may all but devastate this dream41. Migrants seeking an opening into the middle class may have to interminably endure exploitative positions without protections or bargaining power42. Without the qualifications welcomed by the Shenzhen government, workers can spend years of their life in the city without access to key local services such as healthcare43. Skyrocketing property prices exclude most migrants, even highly educated ones, from the ideal of home ownership - while the steady demolition and gentrification of urban villages such as Baishizhou leave migrants with few sustainable options to continue living in the city44.

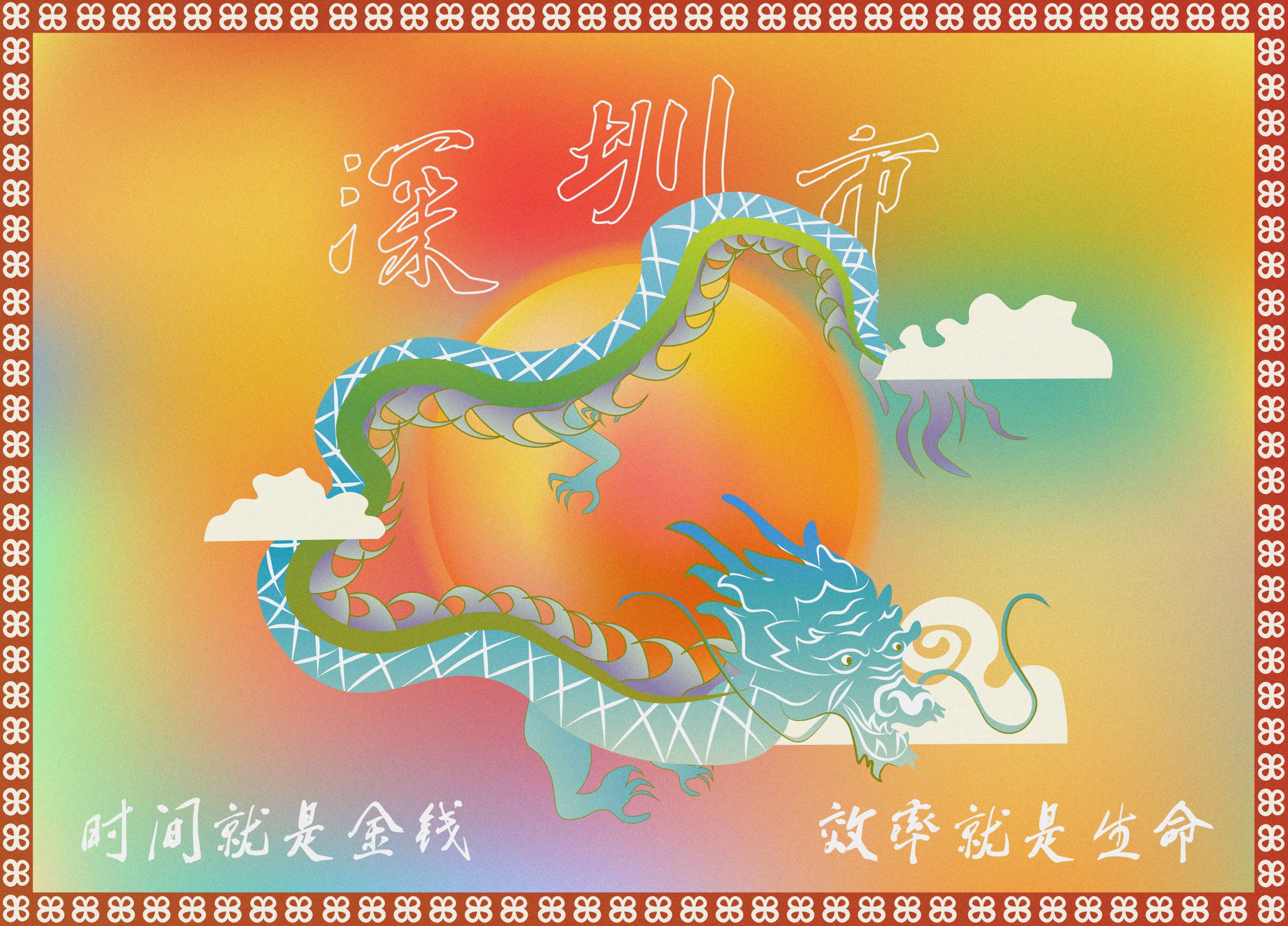

The slogan of the Special Economic Zones and China's economic reform: "Time is Money, Efficiency is Life".

The slogan of the Special Economic Zones and China's economic reform: "Time is Money, Efficiency is Life".

What happens, then, to a dream deferred? For one, we should expect consequences for mental health. Indeed, the lifetime prevalence of depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders in China has been increasing over the last two decades, though at a level still lower than that of western countries45. With some variation from study to study, migrants generally experience a higher prevalence of mental illness relative to urban populations46. While clinical categories are an incomplete indicator of a society’s psychological health, qualitative studies have provided rich description of the feelings of frustration and anomie that can arrive with betrayed expectations47. Quantitative studies which consider non-clinical indicators of mental health such as the World Values Survey indicate that people in China are becoming unhappier - across nearly all income brackets, and for both rural and urban areas. Ever since the 1990s, while living standards in China have improved by a stunning amount, financial dissatisfaction has grown into a leading predictor of unhappiness48.

Women participate in an evening-time group exercise, a common sight.

Women participate in an evening-time group exercise, a common sight.

A group of young people are the only ones eating at a night market in Hubei. The area surrounding the market is a former urban village fenced off for redevelopment.

A group of young people are the only ones eating at a night market in Hubei. The area surrounding the market is a former urban village fenced off for redevelopment.

A widening gulf between expectation and reality is not the sole contributor to China’s increasing prevalence of mental health concerns. Aside from the deepening conditions of inequality we have outlined in this essay, there are stressful events, such as situations of abuse or loss, which may or may not be related to wider conditions. According to the diathesis-stress model, stressful events interact in complex and iterative ways with a person’s predispositions to produce their experienced reality of mental health49. One such predisposition is the cognitive belief in meritocracy or a just world - that rewards rightfully follow effort50. To believe in meritocracy is to implicitly believe that through skill and effort, you can exert control over your reality. This belief, which has and continues to be applied to the realms of work, relationships, and health has now increasingly turned inwards - towards the self.

In recent years, China has experienced a ‘psycho-boom’ of unprecedented proportions, most obviously seen in the expansion of counselling facilities which have become commonplace online and in major Chinese cities51. While these services may still be inaccessible to the general public, the newfound prominence of ‘the psychological’ in Chinese public life is undeniable. Since 2011, mental health has been treated as an explicit target for improvement in the 12th and 13th Five Year Plans. Popular programming such as CCTV 12’s docu-series “Psychological Interview” (心理访谈) depicts the psychological problems of everyday Chinese, illustrating how citizens can work to metabolise suffering into energy for the pursuit of professional success and happiness52. Psychotherapy-related courses and online material are exceedingly popular - many consume them not for the sake of counselling others, but to better understand and manage their own distressing emotions53.

The speed at which Shenzhen's transformation is taking place is apparent in the layers of buildings spotted in Dafen.

The speed at which Shenzhen's transformation is taking place is apparent in the layers of buildings spotted in Dafen.

This renewed propensity towards recognising and managing emotions and the self is at least partially responsible for the higher reported prevalence of mental illness in China. As such, it is welcomed for its potential to improve the lives of those who would have gone on to suffer unnoticed. But we should also view this trend with some caution - not only for the possibility that this may be the blind import of categories and treatments whose validity has been called into increasing question54, but for the danger of applying an undiluted belief of controllability over our own mental health. When confronted with an unfair reality, meritocracy - which inherently implies self-control - wrongly attributes failure to the self’s lack of effort or skill, rather than an uncontrollable external world. This operationalises disappointment into distress. Its corrosive potential here is obvious - so what happens when we apply the belief of controllability to our minds? For many, they may try but find it impossible to ‘optimise’ their mental health - not only because of who they are, but because of the fact that they are living in a deeply unequal material reality. If controllability is taken as truth, it perversely implies that the blame for not feeling ‘normal’ - alongside the cause of failure - is to be found in the individual.

As a state in the semi-periphery, the growing pains of Chinese society are shared by other nations chasing the dream of post-industrialization. However, due to the exceptional speed of its transition, China manifests both the delights and demerits of market economies to an especially intense degree. In many ways, the troubles that plague rural-urban migrants in China are a consequence of greater structural issues within the global economy. The scale of the issue may make intervention seem impossible - or even unnecessary. After all, it is a truism that there will always be winners and losers in the economy, as in mental health - different people may respond to the same stressful event with resilience or retreat. Yet in the words of Arthur Kleinman and Iain Wilkinson: “Human misery, no matter how deeply interior in the individual, is often a collective experience resulting from large societal forces that in turn break neighbourhoods, villages, networks, and families”55. The suffering of individuals may be experienced alone, but it frequently shares a social origin and effect. Thus, it demands social solutions.

In the meantime, the largest migration event in the world will continue to unfold. China’s cities, both small and large, will persist and intensify in their call for migrants. Millions will answer that call by uprooting themselves in the pursuit of better lives for themselves and their families, no matter how unfeasible that dream might be. As we stroll through the busy night time streets of Dafen, scenes of families playing badminton, residents eating and drinking in the square, and a public dancing lesson suggest that in cities designed to exclude, migrants can still construct their own sites of belonging. In the dancers’ movements, we witness the city transformed.

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions and support of those around us. Special thanks to Dr. Christine Gibb, Dr. Kristin Bright, Dr. Teresa Kramarz, Dr. Joseph Wong, Dr. Dylan Clark, Shannon Garden-Smith and Shahd Tashkandi.

Funding for this research was provided through the Richard Charles Lee Insights Through Asia Challenge, a flagship experiential learning program based at the Asian Institute at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. Additional funding was provided by the University College Elizabeth Brown Travel Award.

Citations

- 陈柳兵. (n.d.). Top 10 Chinese cities with highest GDP in 2018 - Chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved September 22, 2019, from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201902/11/WS5c60a841a3106c65c34e88cf_1.html.

- Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2016 National Economic and Social Development. (n.d.). Retrieved September 22, 2019, from http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/201702/t20170228_1467503.html

- Li, J., & Rose, N. (2017). Urban social exclusion and mental health of China’s rural-urban migrants - A review and call for research. Health & Place, 48, 20–30.

- The last days of Shenzhen’s great urban village. (2016, September 29). Retrieved September 22, 2019, from South China Morning Post website: https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/2023255/last-days-shenzhens-great-urban-village

- Wang, Y. A. P., Wang, Y., & Wu, J. (2009). Urbanization and Informal Development in China: Urban Villages in Shenzhen. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33(4), 957–973.

- Lederbogen, F., Kirsch, P., Haddad, L., Streit, F., Tost, H., Schuch, P., … Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2011). City living and urban upbringing affect neural social stress processing in humans. Nature, 474(7352), 498–501.

- Evans, G. W. (2003). The built environment and mental health. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 80(4), 536–555.

- Hao, P., Sliuzas, R., & Geertman, S. (2011). The development and redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen. Habitat International, 35(2), 214–224.

- Hanser, A. (2005). The Gendered Rice Bowl: The Sexual Politics of Service Work in Urban China. Gender and Society, 19(5), 581–600.

- Deep China. (n.d.). Retrieved July 27, 2019, from University of California Press website: https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520269453/deep-china

- Jacka, T. (2014). Rural Women in Urban China: Gender, Migration, and Social Change: Gender, Migration, and Social Change. Routledge.

- Yip, P. S. F., & Liu, K. Y. (2006). The ecological fallacy and the gender ratio of suicide in China. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 189, 465–466.

- Meng, L. (2002). Rebellion and revenge: the meaning of suicide of women in rural China. International Journal of Social Welfare, 11(4), 300–309.

- Deep China. (n.d.). Retrieved July 27, 2019, from University of California Press website: https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520269453/deep-china

- Chan, K. W. (2010). The household registration system and migrant labor in China: notes on a debate. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 357–364.

- Zhou, S., & Cheung, M. (2017). Hukou system effects on migrant children’s education in China: Learning from past disparities. International Social Work, 60(6), 002087281772513.

- Chan, K. W. (2010). The household registration system and migrant labor in China: notes on a debate. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 357–364.

- Meng, L., & Zhao, M. Q. (2018). Permanent and temporary rural–urban migration in China: Evidence from field surveys. China Economic Review, 51, 228–239.

- Meng, L., & Zhao, M. Q. (2018). Permanent and temporary rural–urban migration in China: Evidence from field surveys. China Economic Review, 51, 228–239.

- Chan, K. W. (2010). The household registration system and migrant labor in China: notes on a debate. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 357–364.

- Chan, K. W. (2010). The household registration system and migrant labor in China: notes on a debate. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 357–364.

- Meng, L., & Zhao, M. Q. (2018). Permanent and temporary rural–urban migration in China: Evidence from field surveys. China Economic Review, 51, 228–239.

- Demographics. (n.d.). Retrieved August 14, 2019, from Shenzhen Government Online website: http://english.sz.gov.cn/about/profile/201907/t20190704_18035388.htm

- Chen, C., & Fan, C. C. (2016). China’s Hukou Puzzle: Why Don't Rural Migrants Want Urban Hukou? China Review, 16(3), 9–39.

- Chan, J., Pun, N., & Selden, M. (2013). The politics of global production: Apple, Foxconn and China’s new working class. New Technology, Work and Employment, 28(2), 100–115.

- Labour relations in China: Some frequently asked questions. (2014, November 26). Retrieved September 22, 2019, from China Labour Bulletin website: https://clb.org.hk/content/labour-relations-china-some-frequently-asked-questions

- Labour relations in China: Some frequently asked questions. (2014, November 26). Retrieved September 22, 2019, from China Labour Bulletin website: https://clb.org.hk/content/labour-relations-china-some-frequently-asked-questions

- Labour relations in China: Some frequently asked questions. (2014, November 26). Retrieved September 22, 2019, from China Labour Bulletin website: https://clb.org.hk/content/labour-relations-china-some-frequently-asked-questions

- Migrant interviews, Shenzhen.

- Ngai, P., & Chan, J. (2012). Global Capital, the State, and Chinese Workers: The Foxconn Experience. Modern China, 38(4), 383–410.

- Su, Y. (2010). Student Workers in the Foxconn Empire: The Commodification of Education and Labor in China. Journal of Workplace Rights, 15(3), 341–362.

- Li, S.-M., Cheng, H.-H., & Wang, J. (2014). Making a cultural cluster in China: A study of Dafen Oil Painting Village, Shenzhen. Habitat International, 41, 156–164.

- Shanghai Has Largest Migrant Population in China, but Shenzhen Has the Highest Ratio. (n.d.). Retrieved September 22, 2019, from Yicai Global website: https://www.yicaiglobal.com/news/shanghai-has-largest-migrant-population-china-shenzhen-has-highest-ratio

- Li, J., & Rose, N. (2017). Urban social exclusion and mental health of China’s rural-urban migrants - A review and call for research. Health & Place, 48, 20–30.

- Dong, J. (2009). “Isn”t it enough to be a Chinese speaker’: Language ideology and migrant identity construction in a public primary school in Beijing. Language & Communication, 29(2), 115–126.

- Wu, C. (2018, November 21). How to Get a Shenzhen Hukou - China Briefing News. Retrieved August 28, 2019, from China Briefing News website: https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-hukou-system-benefits-and-application-process-in-shenzhen/

- 马振清刘隆. (n.d.). 获得感、幸福感、安全感的深层逻辑联系. Retrieved September 22, 2019, from CPC News website: http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2017/1215/c40531-29709072.html

- Feng, M. X. Y. (2015). The “Chinese Dream”deconstructed: values and institutions. Journal of Chinese Political Science. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11366-015-9344-4

- Wang, Z. (2014). The Chinese Dream: Concept and Context. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 19(1), 1–13.

- Rofel, L. (n.d.). Duke University Press - Desiring China. Retrieved September 22, 2019, from https://www.dukeupress.edu/desiring-china

- Zhou, S., & Cheung, M. (2017). Hukou system effects on migrant children’s education in China: Learning from past disparities. International Social Work, 60(6), 002087281772513.

- Ngai, P., & Chan, J. (2012). Global Capital, the State, and Chinese Workers: The Foxconn Experience. Modern China, 38(4), 383–410.

- Meng, L., & Zhao, M. Q. (2018). Permanent and temporary rural–urban migration in China: Evidence from field surveys. China Economic Review, 51, 228–239.

- Liu, Y., Geertman, S., van Oort, F., & Lin, Y. (2018). Making the “Invisible” Visible: Redevelopment-induced Displacement of Migrants in Shenzhen, China. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(3), 483–499.

- Lee, S., Tsang, A., Zhang, M.-Y., Huang, Y.-Q., He, Y.-L., Liu, Z.-R., … Kessler, R. C. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and inter-cohort variation in DSM-IV disorders in metropolitan China. Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 61–71. Lee, S., Kleinman, A., Yan, Y., Jun, J., Zhang, E., Tianshu, P., . . . Jinhua, G. (2011). Depression: Coming of Age in China. In Deep China: The Moral Life of the Person (pp. 177-212). Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pnb7k.9

- Zhong, B.-L., Liu, T.-B., Chiu, H. F. K., Chan, S. S. M., Hu, C.-Y., Hu, X.-F., … Caine, E. D. (2013). Prevalence of psychological symptoms in contemporary Chinese rural-to-urban migrant workers: an exploratory meta-analysis of observational studies using the SCL-90-R. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(10), 1569–1581.

- Rofel, L. (n.d.). Duke University Press - Desiring China. Retrieved September 22, 2019, from https://www.dukeupress.edu/desiring-china

- Brockmann, H., Delhey, J., Welzel, C., & Yuan, H. (2009). The China Puzzle: Falling Happiness in a Rising Economy. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(4), 387–405. Lee, S., Kleinman, A., Yan, Y., Jun, J., Zhang, E., Tianshu, P., . . . Jinhua, G. (2011). Depression: Coming of Age in China. In Deep China: The Moral Life of the Person (pp. 177-212). Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pnb7k.9

- Ladd, C. O., Huot, R. L., Thrivikraman, K. V., Nemeroff, C. B., Meaney, M. J., & Plotsky, P. M. (2000). Chapter 7 - Long-term behavioral and neuroendocrine adaptations to adverse early experience. In E. A. Mayer & C. B. Saper (Eds.), Progress in Brain Research (Vol. 122, pp. 81–103). Elsevier.

- Lerner, M. J., & Miller, D. T. (1978). Just world research and the attribution process: Looking back and ahead. Psychological Bulletin, 85(5), 1030–1051.

- Huang, H.-Y. (2013). Psycho-boom: The rise of psychotherapy in contemporary urban China. Retrieved from http://dissertations.umi.com/gsas.harvard:11171

- Yang, J. (2013). “Fake Happiness”: Counseling, Potentiality, and Psycho‐Politics in China. Ethos . Retrieved from https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/etho.12023

- Zhang, L. (2017). The Rise of Therapeutic Governing in Postsocialist China. Medical Anthropology, 36(1), 6–18.

- Clark, L. A., Watson, D., & Reynolds, S. (1995). Diagnosis and classification of psychopathology: challenges to the current system and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 46, 121–153. Cuthbert, B. N., & Insel, T. R. (2013). Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Medicine, 11, 126.

- A Passion for Society. (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2019, from University of California Press website: https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520287235/a-passion-for-society